Conservation is one of the most straightforward yet often misunderstood concepts in economics and common application today. When it is applied to the use of water, it amplifies those misconceptions. In its most basic usage. conservation simply means to use less. In today’s world, however, it is more appropriate to speak of the appropriate management of the resource—in this case, water. This article will use the term management in the context of the application of economics, in which the goal is to use the resource more efficiently. There may be times, as exemplified with recent droughts, where extreme management needs to be applied and no water be used in certain practices. Alternatively, there may be periods, as with floods, where excess water needs to be used in as many ways as possible.

This Fact Sheet is intended to provide an overview of the issue of non-agricultural water conservation in Oklahoma, and to suggest alternative policies and water use practices in the state. Recent research is used to provide the public and Oklahoma water managers with useful information about conservation as a management tool for more effective water use. Oklahomans have experienced both water abundance and water shortages. It is an ongoing challenge for both private and public water managers to plan for the range of extremes from droughts to floods. Often, these challenges have financial consequences that are not insignificant. The era of abundant and free water has passed in Oklahoma.

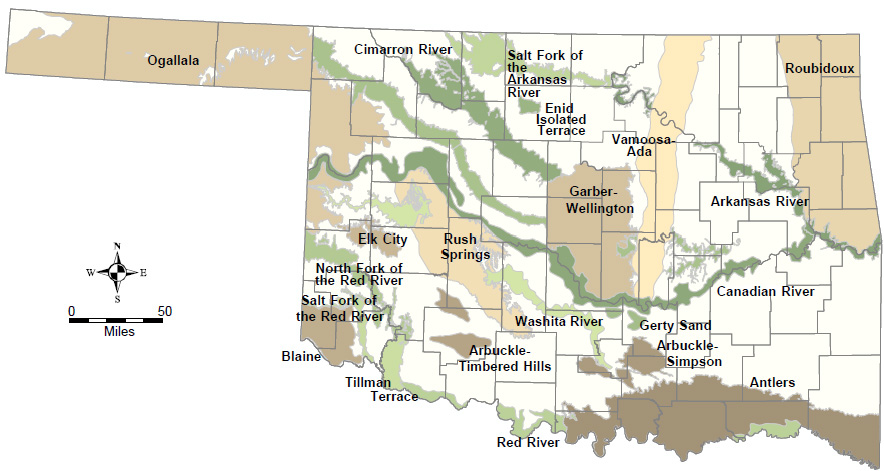

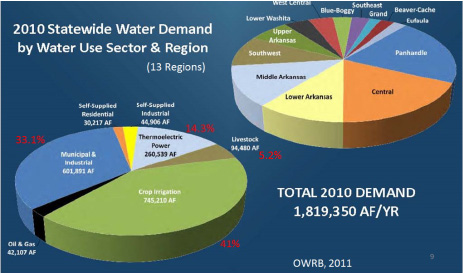

According to the Oklahoma Water Resources Board (OWRB), Oklahoma has nearly 56,000 miles of shoreline along lakes and ponds, containing about 1,400 square miles of water area. The most surface area is in Eufaula Lake with more than 105,000 acres, with Lake Texoma second with 88,000 acres. Additionally, there are more than 167,000 miles of rivers and streams in the state. There are only 2.6 million acre-feet per year of allocated stream water use. In fact, about 34 million acre-feet per year flows out of state via the Arkansas and Red River basins. There are 22 major groundwater basins containing approximately 390 million acre-feet of water in storage, though only one-half of that amount may be currently recoverable (Figure 1). Groundwater is the major source of water in the western half of the state, while most of the surface water is in the eastern half of Oklahoma. The state’s largest groundwater basin is the Ogallala Aquifer in western Oklahoma. It contains 90 million acre-feet of water, nearly one-fourth of all groundwater in the state. Groundwater depletion is currently a problem in western Oklahoma, and this loss is primarily due to crop irrigation.

Figure 1. Major aquifers of Oklahoma.

Concerns about water availability are tied to its cyclical patterns and evolving demands by diverse consumers. When the rains are plentiful, and creeks, streams, rivers and lakes are full or flooding, the concern is about too much water. When drought occurs, citizens hear about gloom and doom. Water availability drives crop choices and yield predictions, economic situations, and political debates. Any given year, estimates suggest Oklahoma has “lots” of water and there is no shortage of water overall because supply far outweighs demand.

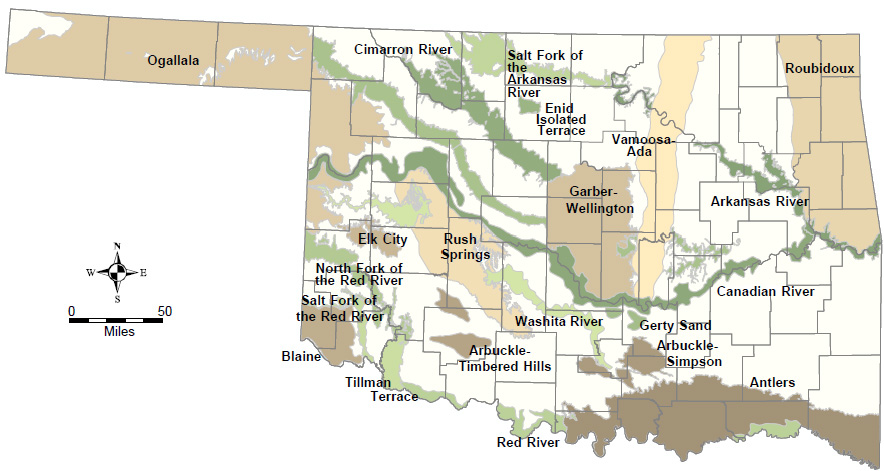

A review of the past 100 years of climate data shows that the last 20 years to 30 years of the 20th century were above average in precipitation for Oklahoma (Figure 2). Producers, agribusiness managers, land owners, public decision makers and others who grew into their careers during that period likely perceived this as the norm, and used that reference point to inform their decisions related to water use and management.

Figure 2. Oklahoma Climatological Survey 100 years of precipitation.

In fact, that period was the aberration. The norm is a cyclical pattern of shifting from wet periods to dry periods every five years to seven years. The first decade of the 21st century suggests the cyclical phase is re-occurring. The long-term chart also suggests there can be annual events that defy the cyclical trend, with a very wet year during a long-term drought, or a very dry year during a cycle of high precipitation. For example, Figure 2 shows an extended wet period from the early 1980s to the early 2000s. This cyclical nature of wetter/dryer periods provides strong incentive to educate the public on the importance of conservation. This educational material is an important part of an ongoing water conservation program.

After five years of research and public input, the Oklahoma Comprehensive Water Plan (OCWP) was approved by the Oklahoma Water Resources Board in November 2011, and presented to the Governor and Legislature in early 2012. The Legislature moved quickly to begin enacting several key provisions into state law by June 2012. The 50-year plan devoted an entire section to water conservation, and the issue was of central concern to the legislative discussion that ensued. Water conservation was one of eight priority recommendations proposing “incentives and voluntary initiatives that strive to maintain statewide fresh water use at current (2012) levels through 2060.” These incentives could include, according to the plan, “tax credits, cost-sharing, tiered water pricing, and other programs to encourage the following activities: improved irrigation and farming techniques; green infrastructure; water recycling/reuse systems; control of invasive species; recharge of aquifers; and use of marginal quality waters; expanded support for education programs that modify and improve consumer water use habits; encouragement of Oklahoma water systems to implement leak detection and repair programs through existing or new financial assistance mechanisms.” The plan further evaluated scenarios of “moderate” and “substantially expanded” conservation measures and found that the moderate measures “could reduce surface water gaps statewide by 25 percent and reduce the number of basins with projected periods of surface water deficit from 55 to 42; reduce alluvial groundwater depletions by 32 percent (from 63 basins to 51); and reduce bedrock groundwater depletions by 15 percent (from 34 basins to 26).” The OWRB website can be consulted for further information.

In response to the completion of the OCWP and its recommendations through the OWRB, the Legislature passed and the Governor signed into law HB 3055. The law creates the Water for 2060 Act, with a focus on water conservation. This includes the declaration “to protect Oklahoma citizens from increased water supply shortages and groundwater depletions by the year 2060 in most of the 82 watershed planning basins in the state … the public policy of this state is to establish and work toward a goal of consuming no more fresh water in the year 2060 than is consumed statewide in the year 2012.” 2 The act relies on voluntary measures and initiatives rather than mandates.

The concepts noted by the bill to accomplish this goal are efficiency and water reuse (waste water, brackish water and other non-potable sources). The law establishes a 15-member advisory council and the Oklahoma Water Conservation Grant Program. The council is charged with making recommendations for such areas as encouraging improved irrigation and farming techniques, education programs to improve consumer water use, financial assistance programs to reduce water loss/waste and encourage consolidation of smaller systems to improve efficiency. While there was no major funding for implementation of this new legislation, it signals conservation will be a key part of the state’s water policy.

Oklahoma water law separates water into three distinct forms: standing, ground and surface waters. Standing water is water running over the ground that has not reached the banks of a streambed, or water that is simply standing on the surface outside of a stream. The owner of the land where this water is found owns the water and generally can use it as they wish. Groundwater is water under the surface, outside of a streambed, that is not saltwater. While groundwater is owned by the owner of the surface land, the use of groundwater is subject to state laws governing its extraction and use. Although groundwater might not appear to impact life and activities on the surface, it can impact stream water and other water sources. Stream water is water inside the banks of a streambed. Stream water is not “owned” by any one party, but is instead regarded as property of the state. Stream water in Oklahoma is managed by a hybrid doctrine of riparian and prior appropriation. Riparian doctrine gives the owners of property adjoining a stream the right to use the water from the stream, and restricts access to streams by those not owning adjoining land. Prior appropriation allows people to apply to the state for an appropriation of water from a stream, even if they do not own land along the stream. When water is in limited supply, those who applied for their appropriations first have priority to the water. The owners of land next to a stream can use the water for a number of household and agricultural uses without applying for an appropriation. If those landowners want additional water, they must apply for an appropriation of the stream water, and parties not owning land next to the stream can apply for an appropriation. When water supplies are low, riparian owners receive the highest priority for their domestic uses, with remaining water users assigned priority based on when they applied for their appropriation.

Oklahoma residents have little incentive to voluntarily adopt water conservation practices. Historically, Oklahoma’s policy in implementing its hybrid doctrine was to put water to use and to prohibit “speculation” or “hoarding” of water appropriations by obtaining water that is not used (in the sense that “used” means taken from the ground or stream). This policy is enforced through the rules governing the appropriations. When a water user is given an appropriation of water, they must report their water use on an annual basis. If they use less than their full appropriation (say, someone appropriated five acre-feet of water and they only use three acre-feet), their appropriation is reduced. This encourages those with water appropriations to use the full amount, even if there are times when some of the water would be more valuable if diverted to another use. This can create challenges when water supplies are low; water users are faced with the decision of whether to conserve water and risk having their appropriations reduced or to use the full amount and risk further depleting the water source. As more and more water users must make do with a limited supply of water, Oklahoma is asking the question: do its water appropriation rules need to be revised to allow for more flexibility in the conservation of its water?

The problem is not about a true shortage of water statewide. Instead, the problem is really about getting water where, when, how much we want, at a quality level, and, most importantly, at a price we want. Given the public-private nature of the resource, a mix of public policy and private decision making is likely to improve the efficient use of the resource.

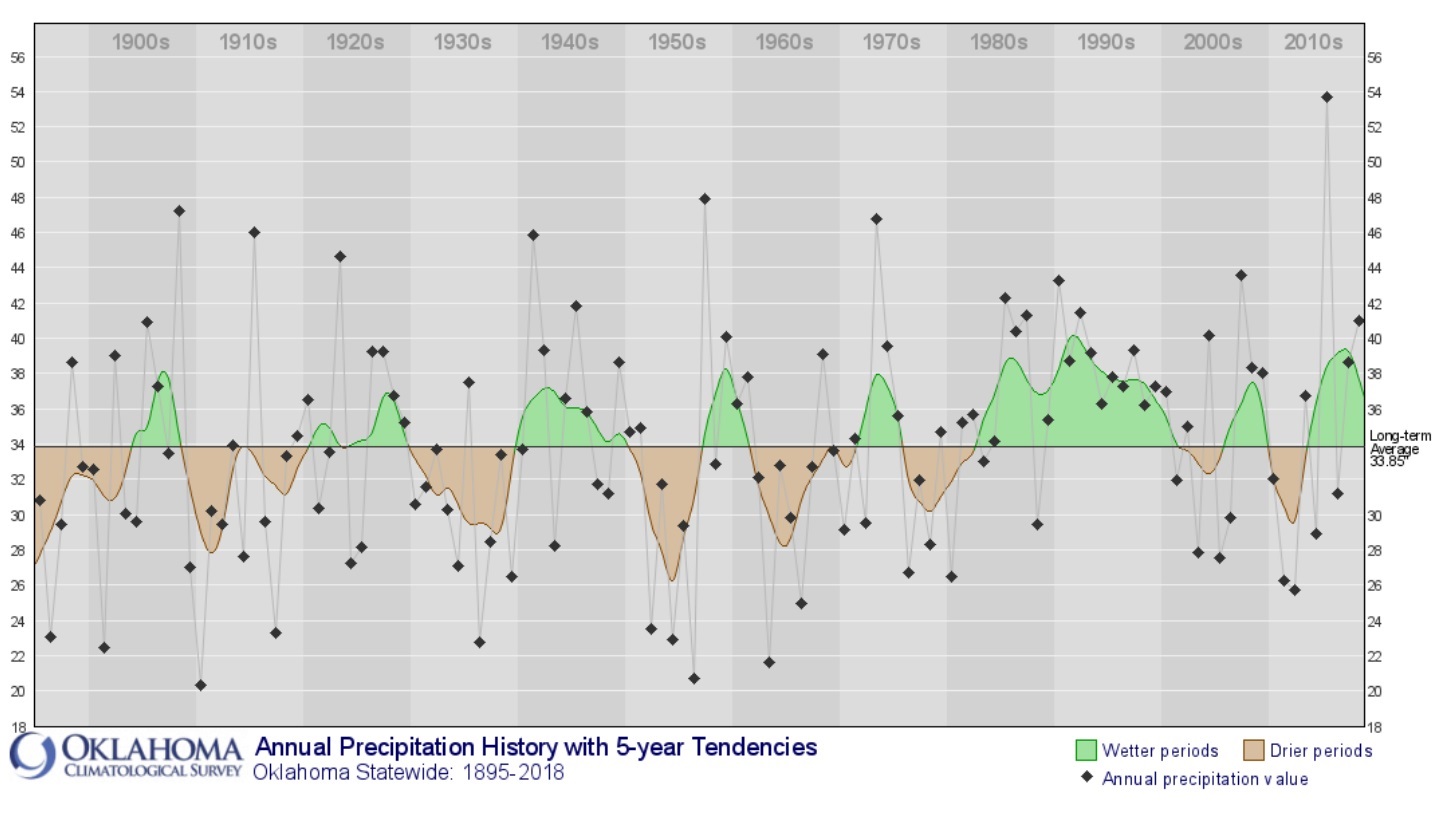

Water as an Oklahoma resource may be termed as abundant, scarce or both, depending on the time, location and use. Droughts bring scarcity. Floods bring abundance. Quality and volume requirements raise questions and concerns about specific uses. Planning and management can improve consistency of water availability for a variety of uses. However, it is clear Oklahoma water is becoming increasingly valuable and a current or potential concern for public and private managers. Oklahoma City Water Utilities, facing critically low supply levels in one of its supply lakes (Lake Hefner) in January 2013, exercised its right to water in Lake Canton upstream. Lone Chimney Lake which supplies towns such as Glencoe and Pawnee remained at critically low levels despite flooding in spring of 2015 and several years of rate increases. Lone Chimney Water Association spent $3.2 million to connect to Stillwater’s water system (Maune, 2015). Agricultural producers and rural land owners have long had a special relationship with and appreciation for water management. About half of all water demand in the state comes from crop irrigation and livestock use (Figure 3). The economic life blood of rural community survival has been tied to water availability since these communities were founded and developed.

Figure 3. Oklahoma water use by sector and region in 2010.

For many water users and managers, the historical solution to water needs has been expanding supply–drill deeper, build another dam, run a longer pipeline. Oklahoma studies have found that water suppliers may be unaware of potential water savings and cost savings available from water conservation alternatives (Boyer and Adams, 2011; Padgett, 2011). Recent research has studied water conservation policy tools as feasible responses to water shortages. There is typically a market failure in the pricing of water because it is usually treated as a free or low-cost resource (See Extension Fact Sheet AGEC-1017) (Hanemann, 1997; Timmins, 2003, Boyer et. al., 2015b). A consumer is normally charged only for the costs of managing the resource–transportation, administration, storage, etc.—rather than the full opportunity costs of its use. (Olmstead and Stavins, 2007). With a price that fails to signal the true cost, efficient water conservation will not occur, unless it is mandated through regulations or compelled by an event that captures the public attention (Howe, 1997). When the price is allowed to rise, it does often have a significant impact on water use (e.g., Pint, 1999). Such responsiveness can vary with season, weather, range of price changes and even show contrary results in the short term. Evidence from Oklahoma City households (2009-2013) shows residential water demand was not responsive to increases in water price except for high consumption periods such as July and August. In the range of the unit water prices of $2.26 to $2.55 per 1000 gallons (3.79 m3), water demand was relatively unchanged. Household parcel size, income and average monthly temperature were positively related to water demand, while rainfall, household age and water price negatively influenced water demand (Ghimire et al, forthcoming). Rainfall had a positive effect on water demand during the drought, perhaps for bathing/swimming or for maintaining the lawns during the drought period. Rainfall during the drought did not eliminate the rain deficit for turf needs. Such results suggest city-specific studies prior to major changes in delivery and cost of water.

While price is typically the most effective tool, there are other methods applied to conserve water in the U.S. (Olmstead and Stavins, 2007; Stevens et al. 1992; Male et al., 1979). Conservation tools include increasing block rates, installing water meters on individual residences and businesses, watering restrictions, incentives for more efficient appliances, etc. Oklahoma City adopted a block rate pricing scheme in 2014 with a higher second tier that would be implemented by 2016 to affect the most wasteful households using more than 10,000 gallons per month (Gotcher, 2014). There may also be questions of fairness and justice regarding the distributional impacts of water policy changes. Consumers do not behave uniformly; some are less responsive to new rules and prices than others (e.g., Schultz et al., 1997; Renwick and Green, 2000). Thus, knowledge about user preferences can help assure selection of policies the public will support and promote effective conservation (Hall, 2000). More public involvement in the policy decision-making process is more likely to bring success in achieving conservation goals. A necessary preliminary step to engaging the public in policy design is education on the issues and alternatives (e.g., Corral, 1997). Alternative methods for collecting public input include surveys, town meetings, forums and plebiscites. Follow-up studies can provide feedback on the effectiveness of policy changes to allow for further changes as appropriate.

Experts agree that the pressure on Oklahoma’s water supply may increase with population growth, environmental regulations and climate change, among other factors. With continuing competition among growing communities to secure their water supplies, and pressure from the rapidly growing urban complex in North Texas, options to conserve Oklahoma’s water resources are worthy of consideration. Although there is increasing experience around the U. S. with crisis-oriented drought response tools, most of this experience has not been shared, evaluated or packaged as conservation policy tools.

Lack of awareness of feasible water conservation policy alternatives presents a significant barrier to development and adoption of contingency plans. Water managers and others need knowledge of: (1) available water conservation policy tools, (2) feasibility for local conditions, and (3) relative costs and water savings. Water conservation can be very cost-effective for water utilities and households. Implementation of water conservation could save households money by adopting off-the-shelf water conserving technologies, assuming current water rates. However, adoption of alternatives to enhance conservation and expand traditional supplies of water, has been very low. This is the case for both price-based and non-price-based water conservation tools.

The primary options for achieving water conservation are to increase the rates (price conservation) or use non-price methods. Rate policies may come in direct price increases or inclining block rates. Non-price policies restrict use, or subsidize conservation practices. A community can adopt either approach or both to manage indoor and outdoor water use. Seasonal pricing rate for the summer months, paying to take out grass lawns or subsidizing efficient lawn irrigation systems are alternative methods for reducing outdoor water use. Inclining block water rate, subsidizing for retrofit of more efficient devices, mandating water meters or replacing aging pipelines are options for both indoor and outdoor water conservation (C. Boyer et al. 2011). A 2013 study of Oklahoma City municipal water customers found older and higher income residents were more likely to adopt indoor and outdoor conservation measures (Boyer et al, 2015a). Surprisingly, neither higher summer consumption during severe drought, nor the perception of prolonged drought increased outdoor conservation adoption of items such as soil moisture sensors and smart irrigation timers. Interestingly, adoption was higher among households owning a heat- and drought-tolerant lawn such as Bermuda. Indoor adoption of low flow faucets, water efficient appliances and low-flow toilets was higher for homeowners, compared to renters and those who expected prolonged drought. Adoption at any level was low for both indoor (32.75 percent) and outdoor (30.98 percent) conservation measures.

Growing communities often find themselves in the situation of increasing quality water supply, while attempting to reduce the rate of use per customer, whether residential or commercial. New sources of water can be expensive, and widespread, successful conservation measures can often be less costly than developing new sources (new treatment facilities, reservoirs, deeper wells, desalinating water, etc.). Water conservation is affected by the perceptions of consumers. Most people do not like price increases or being forced to change behavior. However, education and cultural factors can affect such changes. Change can also be encouraged with policies such as rebates for low-flush toilets or water-conserving appliances, and information about trading lawns for xeriscape, rain barrels and efficient yard irrigation systems. With time and public acceptance, even rate increases may become the preferred option.

Oklahoma’s population will likely grow to nearly 7 million people by 2060. Water conservation can minimize friction among users and reduce the cost of water management. Municipal and industrial users will challenge agriculture and rural water users for more water. There will be increased mining of the aquifers. There will be more challenges from Texas for Oklahoma water. There will be more pressure on maintaining water quality. Energy costs that affect water availability will rise with time. There may be long-term weather pattern changes that bring more variability in water supply. Native tribal rights may force water law changes. The mix of such pressures will likely mean end users will be paying more for their water. Owners of water rights may find those rights evolving with consideration of conjunctive use and pressures for legislative and court modifications.

Conservation is an important part of managing water in Oklahoma, and there is a variety of conservation strategies that communities and regions can choose to implement. Land tenure, wealth, education and attitudes about property rights will affect the likelihood of adopting different water conservation strategies. Future water issues will likely be resolved in the courts and the state legislature. Although some of these decisions may leave many users out of the negotiating process, the active involvement of Oklahoma residents in water law and public water management issues will be important in ensuring that the conservation practices adopted are effective, fair and economical. This does suggest consideration of future focus on water conservation issues and options through the public deliberation process. Public deliberation is a means to help citizens make tough choices about public issues. During a public meeting process, consequences of various options are evaluated and attempts are made to better understand the views of others. The goal is to find a shared sense of direction and common ground for action. The Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service provides development in public deliberation through the Oklahoma Moderators and Recorders Academy.

Adams, D.C., C.N. Boyer, L. D. Sanders. “Alternative Water Conservation Policy Tools for Oklahoma Water Systems”, presentation to Water Research Advisory Board, Oklahoma Water Resources Research Institute, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, July 22, 2010.

Boyer, C.N., D.C. Adams, T. Borisova. “Drivers of Price- and Non-Price Conservation By Water Utilities: A Survey of Water Managers and Application of Predictive Models to the Southern US”, paper submitted to the Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 2011.Boyer, Tracy, Kanza, Patrick, Ghimire, Monika, and Moss,Justin. forthcoming 2015a. Household Adoption of Water Conservation and Resilience Under Drought: The Case of Oklahoma City Water Economics and Policy. Water Economics and Policy. Elsevier.

Boyer, Tracy; Sanders, Larry D.; Adams, Damian C.; Boyer, Christopher N.; Smolen, Michael D. 2015b “Water Rate Structure: A Tool for Water Conservation in Oklahoma.” Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, AGEC-1017. Oklahoma State University.

Boyer, T., B. Tong, L. D. Sanders. “Water Conservation and Soil Adoption in a Highly Erosive Watershed: The Case of Ft. Cobb and SW Oklahoma”, Spring 2015c.

Corral, L.R. (1997). “Price and Non-price Influence in Urban Water Conservation.” PhD Dissertation, University of California at Berkeley.

Hall, D.C. (2000). “Public Choice and Water Rate Design,” in A. Dinar, ed., The Political Economy of Water Pricing Reforms, Oxford University Press, New York: 189-212.

Ghimire, M.; Boyer, Tracy A; Chung, C. and Moss, Justin Q., forthcoming 2015 Estimation of Residential Water Demand under Uniform Volumetric Water Pricing. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management.

Gotcher, M. 2014. “Personal Communication” Water Conservation Director, Oklahoma City Utilities. September 9, 2014.

Hanemann, W.M. (1997). “Determinants of Urban Water Use.” In Baumann, D.D., J.J. Boland, and W.M. Hanemann, eds., Urban Water Demand Management and Planning. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., pp. 31 – 76.

Howe, C. W. (1997). “Increasing Efficiency in Water Markets: Examples from the Western United States.” In T.L. Anderson and P.J. Hill, eds., Water Marketing: the Next Generation. Boulder, CO: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Kimberley Water Expert Panel (2006). “Kimberley water source project.”

Layden, L. 2013. Improving drought conditions haven’t helped Canton Lake recover from OKC withdrawal. StateImpact Oklahoma. Oklahoma Public Media Exchange. (accessed 15 Jan 2015).

Male, J.W., C.E. Willis, F.J. Babin and C.J. Shillito (1979). “Analysis of the Water Rate Structure as a Management Option for Water Conservation.” Water Resources Research Center, University of Massachusetts.

Maune, T. 2015. Lone Chimney Lake Still Near Critical Despite Oklahoma Flooding Elsewhere. June 11, 2015. Newson6 Feature

Oklahoma Legislature, HB3055 Senate Floor Version, Oklahoma Legislature, March 2012.

Oklahoma Municipal League [OML] (2008). “Oklahoma Municipal Utility Costs in 2008.” Oklahoma Municipal League, Inc., March 2008.

Oklahoma Water Resources Board, Oklahoma Comprehensive Water Plan, 2011.

Olmstead, S.M. and R. N. Stavins (2007). “Managing Water Demand: Price vs. Non-Price Conservation Programs.” Pioneer Institute White Paper Series No. 39 (July, 2007).

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (1999). “Household Water Pricing in OECD Countries.” OECD, Paris.

Padgett, M. “Drivers of Water Use and Conservation Adoption by Residential Users in Oklahoma: Motivations, Attitudes and Perceptions”, MS thesis, Department of Agricultural Economics, Oklahoma State University, July 2011.

Pint, E.M. (1999). “Household Responses to Increased Water Rates during the California Drought.” Land Economics 75(2): 246-266.

Reilley, M., T. Boyer, D. Adams. “Using Best-Worst Scaling to Understand Public Perception of Municipal Water Conservation Tools”, poster presentation to Oklahoma Governor’s Water Conference and Research Symposium,” Norman, Oklahoma, November 2010.

Renwick, M.E. and R.D. Green (2000). “Do Residential Water Demand Side Management Policies Measure Up? An Analysis of Eight California Water Agencies.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 40(1):37 – 55.

Schultz, M.T., S.M. Cavanagh (Olmstead), B. Gu and D.J. Eaton (1997). “The Consequences of Water Consumption Restrictions during the Corpus Christi Drought of 1996.” Draft Report (LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas, Austin).

Steinbeck, J. East of Eden, The Viking Press, 1952.

Stevens, T.H., J. Miller, and C. Willis (1992). “The Effect of Price Structure on Residential Water Demand.” Water Resources Bulletin 28(4):681 – 685.

Swales, S. and J. Harris (1995). “The expert panel assessment method (EPAM): a new tool for determining environmental flows in regulated rivers.”In The ecological basis for river management, D. Harper and A. Ferguson, eds. Chichester: Wiley Press, pp 125 – 134.

Tighe and Bond Consulting Engineers (2004). “2004 Massachusetts Water Rate Survey.” Westfield, Massachusetts.

Timmins, C. (2003). “Demand-Side Technology Standards Under Inefficient Pricing Regimes: Are They Effective Water Conservation Tools in the Long Run?” Environmental and Resource Economics 26:107 – 124.

1 Major contributions in research were also provided by Chris Boyer, Assistant Professor, University of Tennessee, and Damian Adams, Assistant Professor, University of Florida Matt Padgett, Matt Reilley and Steve Gilliland, formerly of Oklahoma State University. The authors appreciate the review comments of Dave Shideler and Dave Engle, Oklahoma State University.

Associate Professor, Natural Resources

Larry D. Sanders

Professor/Extension Specialist, Policy and Public Affairs

Assistant Professor, International Economic Development

Associate Professor, Agricultural Law

Professor, Natural Resources